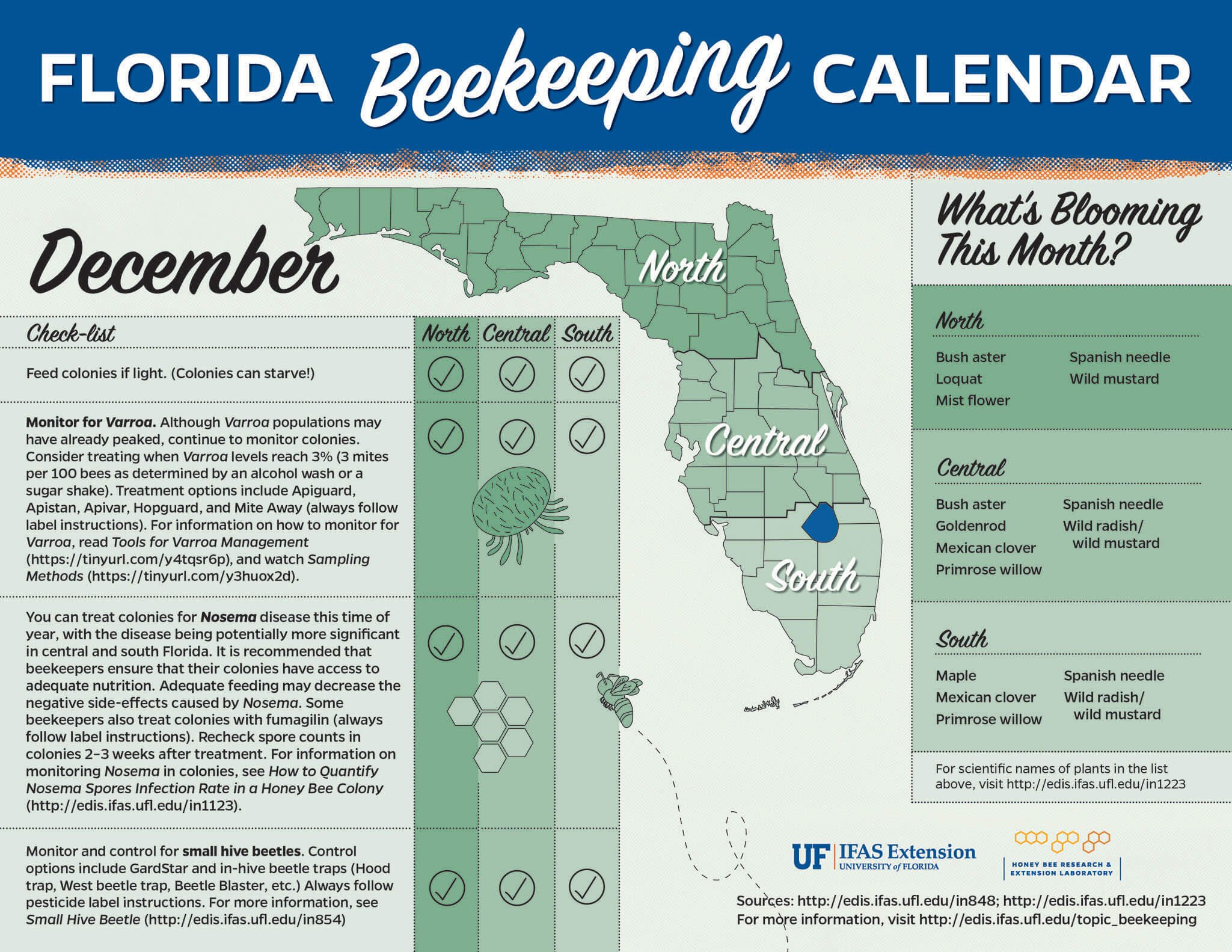

Making a List, Checking It Twice

Winter is a period of preparation for beekeepers. With the citrus flow right around the corner, it can be a scramble to find good queens in time. To reduce stress, here is the most current list of registered queen breeders in Florida, along with their contact information:

Wild Honey Bee Farm LLC - HOLMES VIEW DR UMATILLA, FL 32784, wildhoneybeefarms@gmail.com, 910-546-5066

Michael and Carolyn Peronti - 23539 WOLF BRANCH RD SORRENTO, FL 32776, 407-383-5577

David Smith - 8414 EDISON RD LITHIA, FL 33547, smithhoney2@aol.com, 813-737-3122

Jester Bee Company - 2600 HONEYBEE LN MIMS, FL 32754, order@jesterbee.com, 870-243-1596

Miksa Honey Farms LLC - 13404 HONEYCOMB RD GROVELAND, FL 34736, miksahf@aol.com, 352-429-3447

HR Honey Farms LLC - 40819 W 2ND AVE UMATILLA, FL 32784, HRHONEYFARMS@gmail.com, 352-406-8977

S&S Apiaries LLC - 2429 PIONEER TRL NEW SMYRNA BEACH, FL 32168, nswfljesse@yahoo.com, 386-478-9722

Scott and Marjorie Mansfield - 1018 SE 50TH TER OCALA, FL 34471, scottandmarjoriemansfield@yahoo.com, 352-694-2232

John Sheppard - 5320 LITTLE STREAM LN WESLEY CHAPEL, FL 33545, tranquilhook@gmail.com, 831-915-3863

Sticky Cow Farm Inc. - 4419 SIESTA RD BROOKSVILLE, FL 34602, stickycowfarms@gmail.com, 727-808-7727

Corley Bee LLC - 1110 W LAKE DR WIMAUMA, FL 33598, corleybeeco@gmail.com, 813-690-9808

Snyder’s Hives & Honey - 1844 TIMBERS WEST BLVD ROCKLEDGE, FL 32955, snydershh@yahoo.com, 321-543-2702

Smiley B Farms LLC - 735 GUM CREEK RD GRACEVILLE, FL 32440, allen.scheffer1@gmail.com, 352-538-3182

Lake Indianhead Honey Farms LLC - 25025 BLACK BEAR LN EUSTIS, FL 32736, arussell08@winona.edu, 352-589-1231

John Graf - 9470 ZAMBITO RD N JACKSONVILLE, FL 32210, missbeehaven4@gmail.com, 904-610-3470

Bee Fussy Apiary - 32405 BEACH PARK RD LOT 5 LEESBURG, FL 34788, beefussyapiary@gmail.com, 352-445-2412

Lanko Bee Farm - 227 E BANNERVILLE RD PALATKA, FL 32177, lankobeefarm@gmail.com, 212-365-8801

Millie’s Bee Farm - PO BOX 105 MARIANNA, FL 32447, milliebeefarm@gmail.com, 850-762-2255

Josh Ray - 6514 OLD FEDERAL RD QUINCY, FL 32351, josh.bca20@yahoo.com, 850-510-0401

Seb-Bees LLC - 11727 KENT GROVE DR SPRING HILL, FL 34610, houston3d@hotmail.com, 727-512-4873

Thomas Honey Co. - 14767 N US HIGHWAY 441 LAKE CITY, FL 32055, mike@thomashoney.com, 386-752-6979

Mark Lally - 8181 LAKE LOWERY RD WINTER HAVEN, FL 33880, meel123@aol.com, 863-686-1102

The Barnes & the Bees LLC - 218 NE LAFAYETTE PL LAKE CITY, FL 32055, davidbarnes123@bellsouth.net, 386-965-0990

James and Elizabeth Wessman - 13243 LAVER LN ORLANDO, FL 32824, bottomstungbeekeepers@gmail.com, 321-331-6434

Kranek Apiary - 604 LAKE ARIANA BLVD AUBURNDALE, FL 33823, kranekhome@msn.com, 863-412-6045

Kentucky Honey Farms - 1530 OTTO POLK RD FROSTPROOF, FL 33843, Jakeoz65@gmail.com, 270-993-0146

Heritage Bees - 13339 MJ RD MYAKKA CITY, FL 34251, heritagebees@gmail.com, 813-784-0973

Natural Bridge Honey Farm - 20069 S US HIGHWAY 441 HIGH SPRINGS, FL 32643, mthomas47@windstream.net, 352-284-3971

Flippin Bee Company - 2991 NW 40TH LOOP JENNINGS, FL 32053, flippinbeecompany@yahoo.com, 678-509-4164

Bryan Lee Albritton - 28131 NW 98TH ST ALACHUA, FL 32615, leesbees@rocketmail.com, 386-462-3461

Honey Land Farms II LLC - 22146 OBRIEN RD HOWEY IN THE HILLS, FL 34737, HoneyLandFarms@aol.com, 352-429-3996

Two Brothers Bee Farm LLC - 3319 WILLOW RD WIMAUMA, FL 33598, twobrothersbeefarm813@yahoo.com, 813-786-5048

Dekorne Honey Farms - 1506 BAY LAKE LOOP GROVELAND, FL 34736, djdekorne@Charter.net, 352-429-4687

R Wild Enterprise - PO BOX 591 SAN ANTONIO, FL 33576, radiost256@aol.com, 813-318-2284

Santa Fe Queens - 15815 NW 188TH ST ALACHUA, FL 32615, santafequeens@gmail.com, 903-517-5940

Scott Barnes - 16248 M 216 THREE RIVERS, FL 49093, barnesseven@juno.com, 269-506-5039

Anothony Struthers - 8020 ROSE TER LAKE WALES, FL 33898, astruthers83@gmail.com, 863-205-0019

Bellin Bee Honey Farms - 665 NE 696TH ST BRANFORD, FL 32008, bellinbee1966@gmail.com, 352-874-9626

Indian Summer Honey Farm - 7269 SR 50 WEBSTER, FL 33597, chris@indiansummerhoneyfarm.com, 352-429-0054

Michael’s Bee’s - 1715 N SCENIC HWY BABSON PARK, FL 33827, LLC, michael.bierling@gmail.com, 616-403-6323

Suwannee Farms Inc. - 15445 51ST DR WELLBORN, FL 32094, 386-965-5662

John Knox - 665 NE 696TH ST BRANFORD, FL 32008, buzzingjl@aol.com, 352-542-9776

Simply Southern Bees LLC - PO BOX 1437 NEWBERRY, FL 32669, djellison@live.com, 352-494-9093

Royalty Honey Bees LLC - 39401 SPARKMAN RD DADE CITY, FL 33525, royaltyhoneybees@gmail.com, 352-385-5075

Legacy Honey Bees Inc. - 7090 RIVER RUN BLVD WEEKI WACHEE, FL 34607, mnbbeck@gmail.com, 352-220-4015

Richard Hildreth - 707 NASSAU RD COCOA BEACH, FL 32931, hldr34@aol.com, 321-223-2019

Priceless Health Farms - 5392 NW TWIN PONDS RD MARIANNA, FL 32448, allowaypalms@yahoo.com, 850-762-2555

Jim Sunday - 9010 APALACHEE PKWY TALLAHASSEE, FL 32311, berrypatchhoneybeefarm@gmail.com, 850-661-9320